What are microservices and why are they important

Published on 2014-05-21 20:47:34 +0000

Part of the problem with the debate around microservices is that we aren’t always arguing about the same definition of microservice, probably because not enough of them have read James Lewis’s defining post on microservices. So when two people disagree on the implementation details of the microservice, they can be speaking at cross purposes because they haven’t agreed what they are talking about.

Because I’m going to write more about microservices, why I think it’s such an important architectural movement, and why I think it ties into other movements, I feel like I need to set out my definition of a microservice, and what things are supporting practices that aren’t about microservices, but help to make microservices such a useful pattern

What is the microservices pattern?

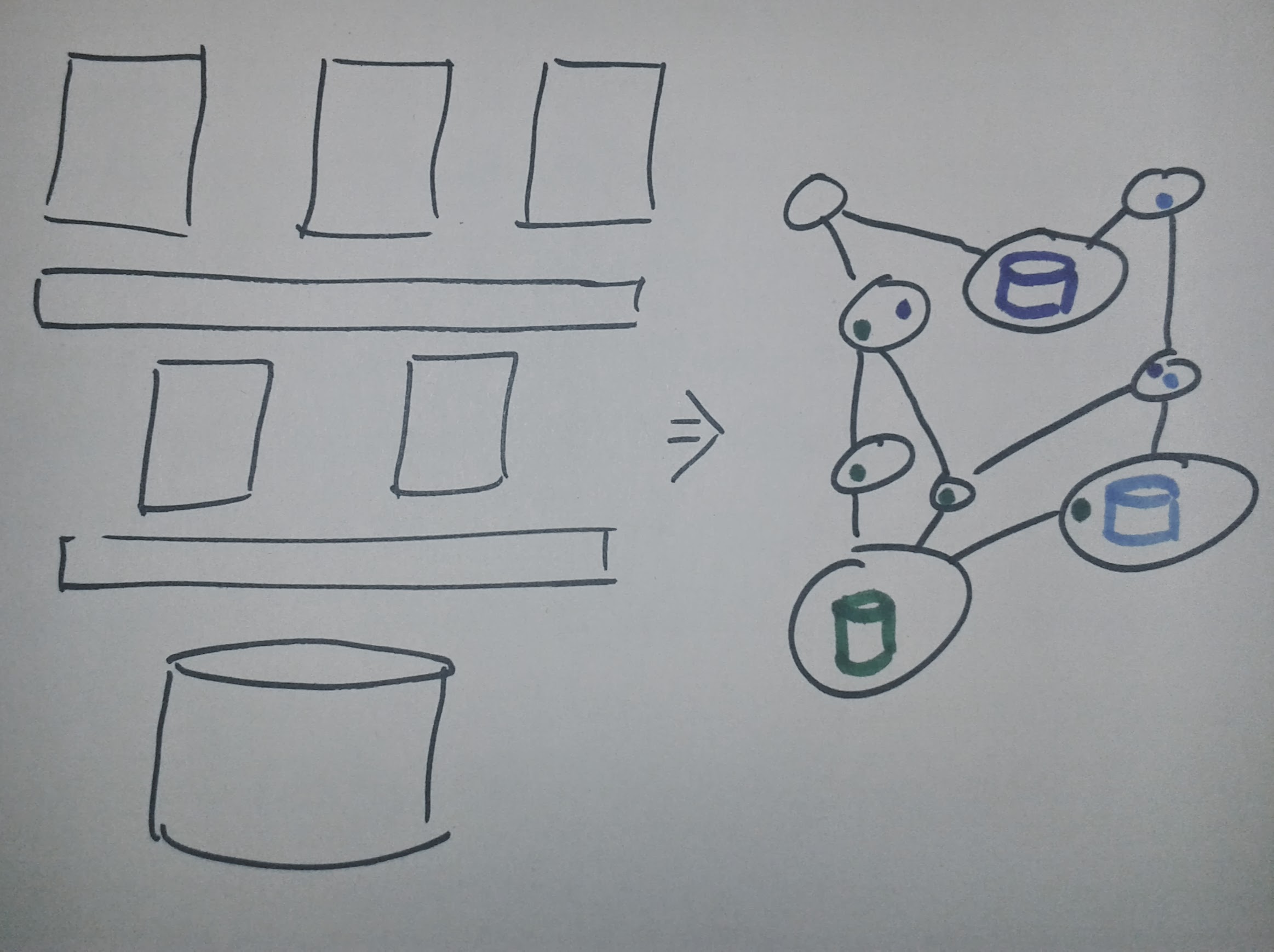

My definition for a microservice is:

- A small problem domain

- Built and deployed by itself

- Runs in its own process

- Integrates via well-known interfaces

- Owns its own data storage

A small problem domain

I argue that a microservice is only really micro if it deals with a small domain, ideally doing just one job or function. The entire service should be conceptually understandable by anybody who needs to pick it up and work with it, either through it’s expression in code, or it’s public interfaces.

This tends to lead to fewer lines of code, although I’m sure exceptions sometimes happen for particularly complex domains. I’m always hesitant to put numbers on things like this, because 50 lines of Python is not the same as 50 lines of Java, but I’d suggest that if the total service is more than 500-1000 lines of code across 5 or so domain objects, then you may want to re-examine the breakdown of your services.

Built and deployed by itself

Each microservice should be standalone, it should be possible to build and run the service in complete isolation from any other services or systems. That makes your service easy to test in integration terms and reduces the complexity of the entire system.

Obviously, some services will require the use of other services, and there are patterns around shared facilities, like auditing, load balancing, transactional consistency, monitoring and so forth that your service may be able to make assumptions on.

The value of this in production is that the size of a change can be very small, and deploying lots of small changes continuously has significantly less risk than large complex changes.

Runs in its own process

The services should each run standalone. This allows you to change technology stack for each service, for example you might build a high throughput service in golang for efficiency, and a transformation pipeline service in Clojure. Because each service runs in its own process, the choices don’t affect one another.

I commonly see microservices running on their own server, but with the rise of virtualisation, and tools like docker, the concept of a server is a bit vague now. I’m not sure that it’s that important to run them on their own server as compared to ensuring they are separate processes.

Integrates via interfaces

Microservices are loosely coupled vertical stacks. Each microservice should communicate with other services via well known interfaces. There’s a lot of disagreement about whether this should only be standards like HTTP or other well known interfaces. I think the important thing here is that the service should replaceable with another service written in a different language. This rules out standards like Java RMI that are bound to the language implementation.

I think that standards like Thrift RPC, Protocol Buffers as well as using message queues or notification services are good integration mechanisms. One of the big advantages of integrating at well defined interfaces is that stubbing out entire services for testing purposes can become much simpler. You can define a mock service that follows the interface and during the test, the service under test can just call your mock. However that might require some way to work around service discovery and test injection.

Owns its own data

The ability to own your own data model is the key to microservices in my mind. Integrating or communicating at the database is always a bad idea, When you don’t own your data, you are unable to freely modify the data layout, and you require significant coordination between systems to make changes. Furthermore, the primary issue here, is around where multiple systems use the database as a point of coordination or communication. That’s what tends to cause the biggest problem.

A microservice should be able to change datastores, use polyglot persistance across multiple datastores with different behaviours, and to worry about it’s own consistency behaviours internally. This isn’t about creating multiple systems of records, a microservice should be responsible for it’s own data, meaning it is the system of record for the aggregate roots involved in the services domain.

It should be obvious that not all microservices are equal here. Some services are responsible for data persistance, some services are consumers of other microservices and responsible for data presentation. The services responsible for data presentation don’t own the data at rest in a datastore, primarily because they wont have a datastore.

Why now?

Why is it that people are talking about microservices now? It’s been nearly 15 years since the concept of Service Oriented Architecture really took hold (I remember attending a session run by Microsoft where they explained that Web Services would be the key to the future). However in that intervening time we’ve had several significant changes in the way we think about architecture and the way that we build interconnecting systems.

Eric Evan’s brilliant book on Domain Driven Design has helped technologists learn how to do a better job of modelling a business process in software. Specifically the concepts of Aggregate Roots and Bounded Contexts give us a great way of breaking up a domain into microservices, with a service interface between each context, and ensuring that a service is responsible for an aggregate root and all of it’s child domain objects.

REST style interfaces and JSON as a data interchange format has made it easier than ever to build easily interconnectable services simply and quickly.

Micro web frameworks, such as Sinatra, Flask and so forth have made it easier than ever to build very simple web services, as compared to fully featured frameworks that bring everything with them (like Spring, Django or Rails).

The downsides

There are always downsides to any architectural approach. One of the skills of an architect is being able to weigh up the pros and cons of the various options open to you and picking one. I therefore believe that when we talk about approaches like microservices, we should be open and honest about the downsides as well.

Microservices trade complicated monoliths for complex interacting systems of simple services.

A large monolith might be so complicated that it is hard to reason about certain behaviours, but it is technically possible to reason about it. Simple services interacting with each other will exhibit emergent behaviours, and these can be impossible to fully reason about.

Cascading failure is significantly more of a problem with complex systems, where failures in one simple system cause failures in the other systems around them. Luckily there are patterns, such as back-pressure, dead-man’s switch and more that can help you mitigate this, but you need to consider this.

Finally, microservices can becomes the solution through which you see the problem, even when the problem changes. So once built, if your requirements change such that your bounded contexts adjust, the correct solution might be to throw way two current services and create three to replace them, but it’s often easier to simply attempt to modify one or both. This means microservices can be easy to change in the small, but require more oversight to change in the large.

But what about production access, team sizes and so forth?

When we talk about microservices, we often conflate a few supporting approaches at the same time. To get the most benefit out of microservices, you need DevOps principles at work, ensuring that the teams own the service in production, and have the ability to change the service.

I think that microservices work best when worked on by small multi-disciplinary teams. However, I don’t think that these practices are a fundamental requirement of microservices. Instead I think that in a catch-22 like situation, to get the best out of microservice architectures, you’ll adopt these practices, and I feel like these practices are most effective on microservice based architectures.

Is it possible to build microservices where you throw them over the wall to an Ops team, where the team consists only of App developers, and the UI design is done by a different team? Sure I do, I’ve done it at the Guardian, and we gained lots of technical benefits around scalability, reliability and ease of modification. However, once we started changing the ownership of the deployment process, the system in production and encouraging the sys admins to be part of the project teams, only then did we start getting significant benefit from microservices.

So why are they important?

So given all of those downsides, what’s the reason that I think that microservices are worth investing in and using?

For the first time in a long time, we have an architecture that is predicated around being easy to change in the face of changing requirements. Agile development is all about embracing the inevitable change, but this architecture makes it easy to do so.

Somebody changes some data fields for a domain object, simply update the service that controls it to accept those new data fields, release it and then change the other services that call it to add the data fields.

Suddenly small code changes and large architectural changes are easier to achieve and easier to organise across those context boundaries.

I think it also works hand in hand with small multi-functional teams owning their services in production, which gives greater ownership, responsibility and therefore better value for money.

Thanks to @matwall, @kushalp, @jystewart, @jabley and @ade_oshineye for reviewing and feedback. All opinions and errors are mine, so don’t blame them