Alpha to Live is not a linear progression

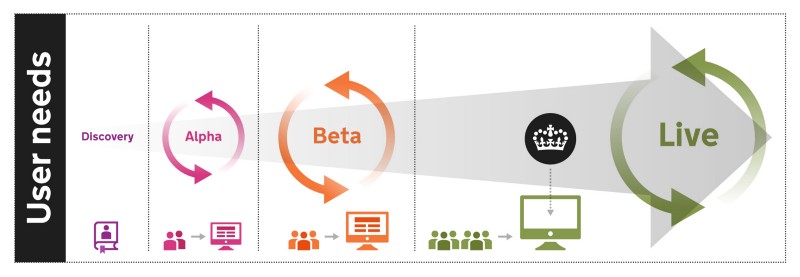

Published on 2017-11-06 21:22:46 +0000I’ve always felt like the diagram that shows the linear progression of a project from discovery through to live, which GDS constructed to demonstrate the lifecycle of an agile project had a pretty critical mistake in it.

I think this was misaligned to how people perceive project lifecycles.

It’s true that if you look at a live service, you should be able to trace the service back to a discovery, but that doesn’t mean that any given discovery should result in a single live service.

Why is it such a problem?

A traditional project lifecycle according to best practice (Prince2 or ITIL or whatever you prefer) tends to look something like this

](/images/uploads/1__uVXjJUlw5r1k6ghWE0TAbQ.png) Image from https://projectmanagementvisions.wordpress.com/2014/10/20/what-does-project-life-cycle-mean/

Image from https://projectmanagementvisions.wordpress.com/2014/10/20/what-does-project-life-cycle-mean/

To someone who was from that world, who had always dealt with traditional projects, it looked a lot like GDS had taken their existing process and given each phase new names.

This means that for many people attempting to shake up project and service governance in Government, they felt that they understood where we were coming from.

But the GDS diagram misses the funnel, showing fewer and fewer projects at each level, and while it attempts to show iteration within a phase, it strongly implies that projects will always progress forwards, just like they always did before.

This means that people entirely seemed to misunderstand the purpose and intent of the original phases, and what the expected outcomes were supposed to be. This is why I think it was such a big mistake.

GDS was trying to get people to think about services and service delivery rather than projects, but this diagram just reinforces the old thinking and makes it look like the new agile model is just an iteration on the old one, rather than a paradigmatic shift in thinking.

What is a discovery for anyway?

A discovery process is about understanding the user need and the realm of the possible entirely unconstrained by thinking about how to solve the problem.

A discovery should be about trying to understand the landscape, find the users and get to understand what actually drives their user needs. It’s about opening up that information and synthesizing it into a consumable form for the rest of the organisation to better understand what is going on.

As Richard Pope outlined in his blog post, Product Land, the world of possibilities is open to you. Teams often focus on discovering and prototyping the solution, rather than using those activities to understand the n-dimensional problem space, and then possible solution maps.

A discovery probably needs to be divided into two phases, a longer phase of problem discovery and elaboration, and then a short phase of synthesis and potential next actions brainstorming.

This leads to another problem, one that is highlighted by the GDS graphic that shows the linear progression from discovery to alpha.

Discoveries should lead to multiple outcomes

At the end of a discovery, there should be a whole set of recommendations, including further discoveries, multiple possible prototypes to test, and recommendations for non service building work.

It might also suggest that the problem doesn’t need solving, or that there is no value in doing further work. If that’s the case, then congratulations, you succeeded, go make yourself a cup of tea and get started on solving a new problem.

An output of a discovery could include:

- Work with comms and engagement teams on conference talks, networking events and other ways to educate, inspire and engage

- Commission work with user groups, think tanks

- Initiate new discoveries into other areas

- Some potential prototypes for solutions (Alpha’s)

A discovery may well suggest that there is a user need that is not being met, and that building a prototype to meet that need would be a good idea. But a discovery should not constrain what solutions are possible, and should leave open the ability for new prototypes to be created.

It’s also worth remembering that learning is valuable in and of itself. It might be sufficient that you have improved the organisations understanding of the problem, and no further work is necessary. Of course to make this really valuable, one might need a good way of actually circulating this research. I might suggest that looking at the academic sector, and the ability to publish research, have it peer reviewed and referenced is something Government should aim for.

Alphas are prototypes, not the first n weeks of the project

One of the things I wanted to get into GDS’s guidance for alphas, and never did, was that at the end of an alpha, you should throw away all of the code. For example, at the end of the alphagov project to prototype what the GOV.UK website might look like, GDS threw away almost all of the prototype code.

An alpha should be an entirely exploratory process, one where you shouldn’t feel constrained by having to write fault tolerant, repeatable and reliable code.

Instead we want teams to move fast, to explore the possible solution space and feel confident that they’ve learnt more about what possible solutions there are and which ones should be progressed.

Alphas could be as short as 2 or 3 weeks (if you can iterate your design and user testing that fast), or as long as 12, but the entire purpose of the alpha is to give you sufficient knowledge to propose a much larger project, be able to better predict the costs, the complexity and have some confidence that it would achieve its aims.

It’s entirely possible and even reasonable that instead of teams running a single long alpha for 12 weeks, that they run 3 alphas of 4 weeks each, each with a different focus or hypothesis. For example, one might look at the user experience of a potential solution design while another looks legacy data interconnection problems. These two alphas might need different skills and teams and have very different outcomes at the end!

My rough take is that I think no more than 50% of the alphas projects that we put together should lead straight to a beta project, and in some places, I’d like that number to be 10% or even 5%. That’s right, only 1 in 20 alphas should “be successful”, meaning that they lead to a beta project being run.

My reasoning is that in a lot of places, the ability to rapidly prototype and test a variety of solutions to a problem would enable much more out of the box thinking.

If you know that the idea you are going to test in your alpha is the one that is going to be funded for your beta, then there is a massive pressure to get it right.

If there’s no pressure that this one idea will be the start of a massive beta program, you are more likely to try ideas that might fail. If only 50% of alphas progressed to beta, then you only need half the confidence that this is the “right” idea, if only 1 in 20 alphas progress to beta, then you can try even more outlandish ideas that might only work 1 in 20 times.

If we want digital teams to be bold, to fail fast and to try radical new ideas, then we need to actively enable and encourage failure.

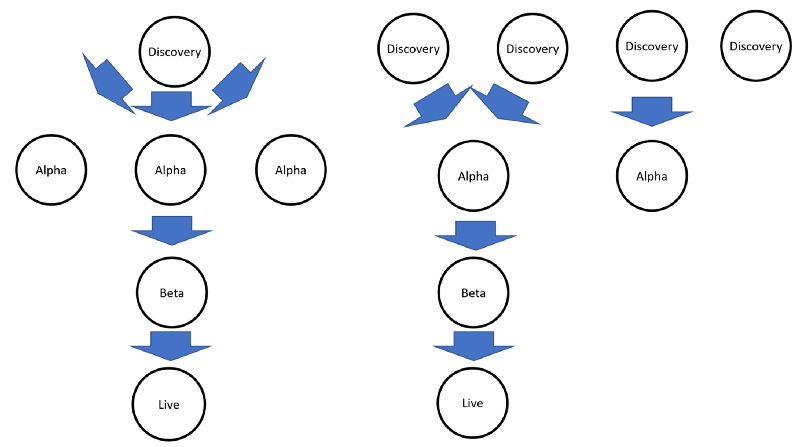

What should it look like?

Organisations should start many discoveries. Discoveries should lead to sometimes one, sometimes many and sometimes no alpha projects being started. Some of those alpha projects might lead to a beta service being produced and live services should come from the successful beta services.

Sometimes a good idea at the wrong time shouldn’t be pursued

The other point about not progressing projects to beta is that it’s not only solution fit that is needed for a project to go ahead.

A successful beta or live service can only go ahead if you have staff, money, resources, political backing, capability and capacity.

If you are currently running 5 major projects, and there’s a really good idea for a 6th, you either need to grow the capacity to run another project, shutdown one of the existing projects, or choose not to progress with the project.

It doesn’t matter how good the idea is, how well it will fill the user need, as an organisation, we have to be careful about what we do.

The user need might still be there, and we might need to find a new way to meet it, but just continuing a project because we’ve got sunk cost in building it is such a common issue that it’s an eponymous fallacy

The best performing organisations are lean and focused on what they do, it’s as much about what you say you won’t do as what you say you will do.

What about Beta?

Beta’s are where the real project work starts to come in. A Beta program is a significant amount of work to build the production like capability to run a real service.

The alpha and discoveries that preceded it will have informed the decisions made and enable the project to have a high liklihood of success.

So why a beta?

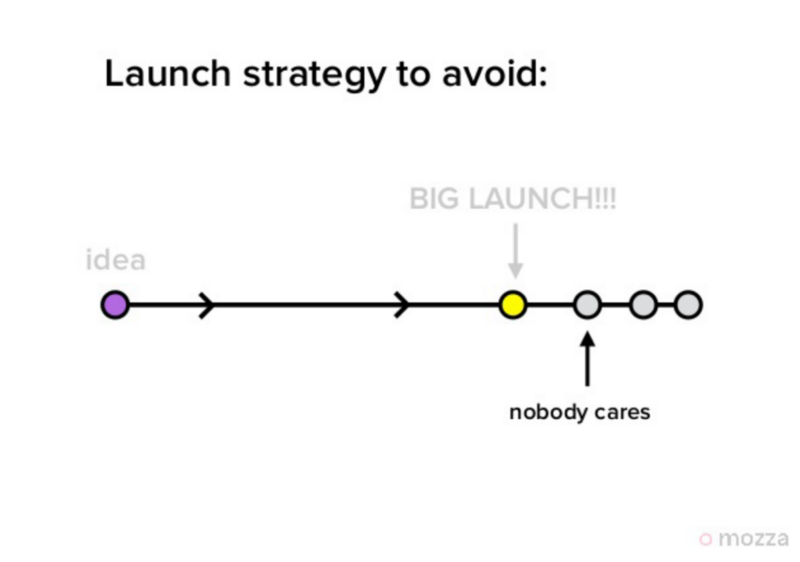

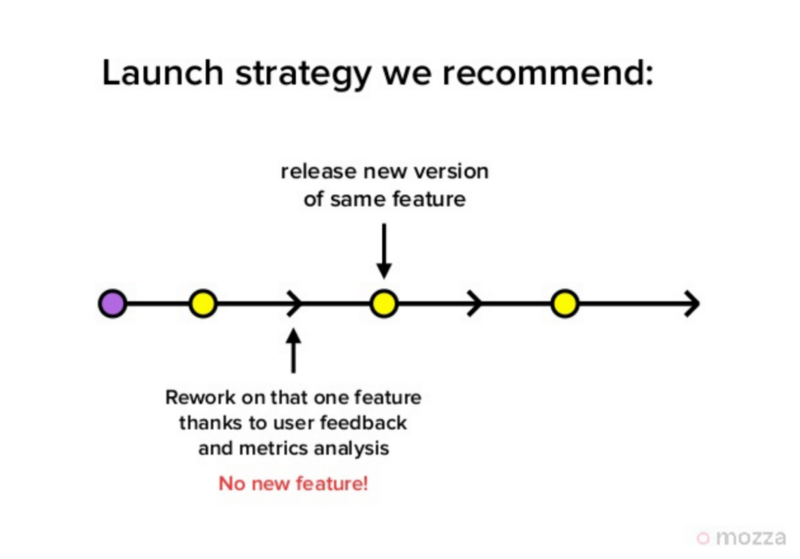

Well, this is about the way to approach launching any product that is designed to meet user needs.

This analysis of the growth of Snapchat, in particular slide 18:

This diagram does a great job of showing why taking the journey from idea to launch doesn’t work. In comparison, when you roll out the minimum viable feature set, you can get fast feedback. We do this by building a beta service that either has a reduced feature set, or a reduced audience or both.

When should a beta not lead to a live service?

The entire point of doing the discovery and alpha work is to derisk the beta service. It should be the case that in a lot of cases, something that has got as far as beta should find no significant blockers to building a good service.

However, we aren’t all perfect, and we can’t predict the future. The users needs might change, the technology or environmental context might change, or there might just be something totally unforseen (such as a snap election or referendum result).

In those cases, we might find while building the initial minimum viable service that the service we are building isn’t viable, the approach we are taking isn’t working, or the context has changed beyond what we discovered early on. If that’s the case then we should either stop the project, or pivot the project to actually meet the user need.

We should be proud of when we do this. We haven’t failed, we’ve successfully saved the taxpayer money by not throwing good money after bad, and we’ve done so fast, and safely.