Getting started in programming with Advent of Code and Python

Published on 2018-12-03 10:47:29 +0000Have you always wanted to program? Have you been interested in the dark and mysterious ways of development? Maybe you’ve done some reading, done a bit of practice, but haven’t been able to find the motivation or the right kind of thing?

For me, development and programming is all about problem solving. I love a good problem, and I like thinking of ways to solve them. One of the reasons that I don’t program enough, apart from being a manager these days, is that finding arbitrary problems to solve isn’t very easy.

That’s why I love Advent of Code. It’s an annual challenge that pits you against a set of programming problems, but each one is scripted against a Christmas themed story. There’s a community of people who approach these problems for a variety of different reasons, from wanting to be first on the scoreboard, to wanting to learn how to approach problems in a brand new language.

I like to do them because the problems are somewhat abstract, but also grounded in a fun story. They are often slightly mathematical, in that there are some very good ways to solve them efficiently, but most of them can be solved in very naive ways as well, which is great for learning and practicing.

So, assuming you’d like a go, I’m going to walk through how you might get started this year. I personally like to use the programming language Python to solve these kinds of problems. It’s simple to learn, it has built in most of the functionality you will need, and it’s preinstalled on a Mac, so there’s very little fiddling around to do to get started.

So lets go

Install anything extra you need

You are going to need 3 things to start day 1.

- A text editor

- Python installed

- A github account

A text editor

You can choose a text editor of your liking. On a mac, you can press Apple-Space and type ‘textedit’ and you’ll get the built in text editor. On Windows you can use notepad.

While textedit or notepad will do the job, you’ll find life a lot easier if you install a programmers text editor. Why? Because they understand that you are trying to program and that’s different to just typing normal words.

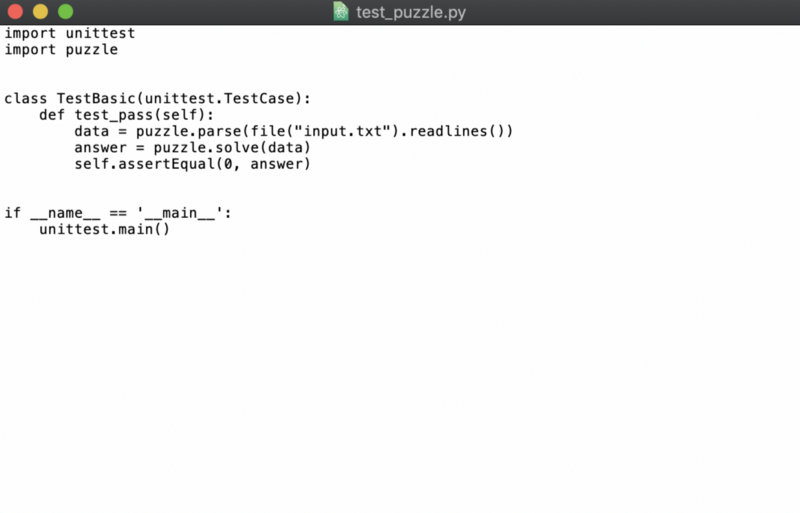

Python code in TextEdit on the Mac

Python code in TextEdit on the Mac

I’d recommend using something like Atom or Microsofts VSCode. Both are completely free, simple to install and both come out of the box with something called “Syntax Highlighting”. That means that it will put any reserved words or symbols into a different colour.

The primary help for a beginner with syntax highlighting is that it will warn you if you forget to close a bracket or a quote mark somewhere, because all the following text will be a single colour. It’s very helpful, so go to one of those sites and install that software, it’s simple and easy.

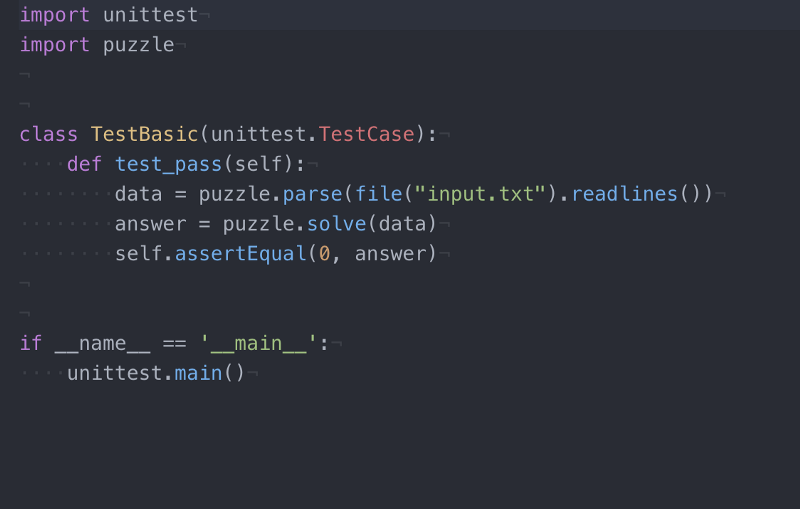

The same code in Atom. See the colours showing strings, special words etc

The same code in Atom. See the colours showing strings, special words etc

Both should install just fine on windows or Mac (I use a mac, so the windows instructions in here won’t be as good I’m afraid)

Installing Python

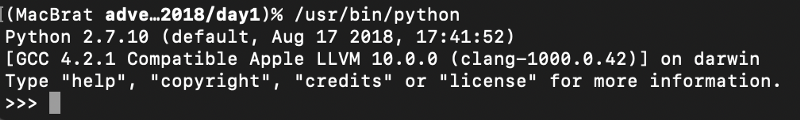

Next we need python installed. Luckily for Mac users, python comes pre-installed on a mac. Press Apple-Space and type “terminal” and you should get a terminal window come up. In that window type “python” and you should see something like this. (This is called the REPL)

Python on the mac, ignore the /usr/bin bit

Python on the mac, ignore the /usr/bin bit

At this prompt you can just type your code, and see what works. Type 2+3 and it should print 5 for example.

Hold down the ctrl key and press D to quit the REPL when you are done

If you are using windows, go to the Python website and follow the instructions

While you can use the Python REPL, it’s not recommended. What we do most of the time is type our commands into a text file, and then run the file using python. This makes it easy to correct the code if you make a mistake, which you will do, and run it again.

Every developer is different on how they arrange their code, so you need to work out what works for you. I personally have a directory in my home directory called “work” and in there is a subdirectory for each project I work on. I created a directory for the advent of code 2018, and then I create a directory for each day.

But before we get there, we should discuss version control.

A github account

In order to get into the advent of code you need to sign in. They let you sign in with Gmail, Twitter and your Microsoft account if you want, but you should take this opportunity to get yourself a github account if you don’t have one already.

Github is where almost all developers in the world store their code. There are alternatives, but it’s a good start. If you ever want a job as a developer, a lot of places will look to see if you have a Github account as part of the screening process.

To sign up, go to Github and hit the sign up button. Come up with a name for yourself. Remember that this might be your professional identity in future, so keep it clean. For years I was MIB because I only wore black, but as I realised that this would be professional, I changed my online presence to be bruntonspall everywhere. It doesn’t have to be your name, and for most people probably shouldn’t be.

Now, we have a choice at this point. I would recommend keeping all of your code on Github and regularly pushing and storing it there as you go. But I don’t want to cover using Git and GitHub in this tutorial, so if you want to do that, go read something like this or get a friend to help.

If you are using github, then create a repository called AdventOfCode2018 and then clone it into your work directory. If not, from that terminal, type mkdir work to create the work directory, and then cd work and mkdir AdventOfCode2018

Also, go to the Advent of Code website, sign in with Github and click day one and you should be able to read the problem

Lets get started with Python

Right, we’re going to program now. Before we start properly, I’m going to suggest the way that I structure my code. There are other ways of doing this, but this works well for me for this kind of coding problem.

Firstly, I use something called unit testing to explore the problem. Python comes with a module of code called unittest which does most of the hard work for you, and makes it easy to describe tests.

I write tests for my code before I implement them, and then I run the tests to be sure they fail for the right reason. As I go through the problem, everytime I encounter a bug or weirdness, I create a new test to document what I think should happen.

Lets take day one as an example.

We have been given a set of numbers to sum up. These look like +1, -2, +1 and we need to add them all together and get the correct number.

So I created my first test to look like this

def test_basic_solve(self):

data = [1, 1, -2]

self.assertEqual(0, puzzle.solve(data))

Ignore the syntax and how it looks, the critical thing here is to see how the test is structured.

First I create the data in the form I want. (We’ll cover the syntax in a bit)

Then I use a method called assertEqual to compare my expected result 0, with the result of calling my code puzzle.solve(data).

If my code didn’t account for negative numbers correctly, then this would fail my test. If it didn’t count correctly, it would fail the test, and so on.

For my first try, I made the puzzle.solve just simply always return -1, so my test failed. I can now write the code in puzzle.solve and know that when I get it right, the test will pass

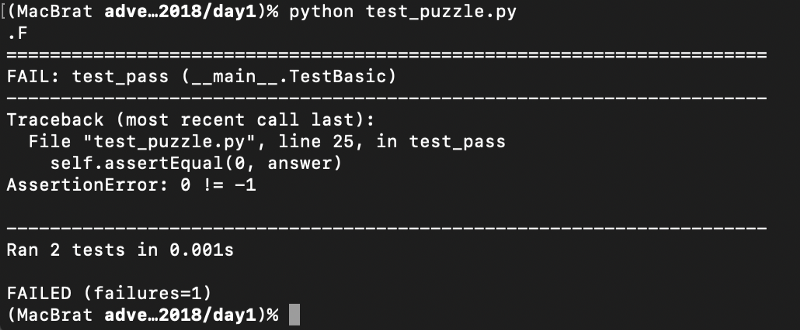

I run the tests by typing python test_puzzle.py in my terminal, and it shows me which ones have passed or failed.

Structuring your code

Python allows you to structure your code into 3 different concepts, modules, classes and functions. I use all three in my template code, and I’m going to explain how and why that works.

Firstly, in python a file contains code into a module. If I create a file called myfoo.py that has some code in it, then in another file, say mybar.py I need to bring that code into scope to be able to call it. I do this by putting an import statement at the top of my code. import myfoo will bring that code into scope for my file.

Inside a file, code in there is run when the file is either called by typing python filename or when the code in a file that is run that way says import myfoo.

Normally we don’t want to do that, so we bundle our code up into functions. A function is a piece of code that takes some arguments and normally returns a value. It’s a good way to divide up your code into neat segments that do different things.

In python we define a function using the def keyword, and the format looks a bit like this:

def my_func(a, b):

return a+b

In this case we’ve defined a function called my_func. We’ve said it takes two arguments, which we’ve called a and b.

When the function is called, you can essentially assume that we replace a throughout the indented code with the first argument and b with the second argument. So if we call the function by writing elsewhere my_func(2,3) then a would be replaced with 2 and b replaced 3.

Return is a special keyword that says stop processing the function and return back the value on the right. In this case, the sum of a and b together (or 5).

Finally classes. I don’t use classes in Python very much for this kind of coding because we tend not to be building systems that are complex enough to need them.

But the testing framework requires one to exist, but I’m not going to explain it, just show you what I do.

Here’s puzzle.py

def parse(lines):

return None

def solve(data):

return -1

Here’s the test_puzzle.py file

import unittest

import puzzle

class TestBasic(unittest.TestCase):

def test_pass(self):

data = puzzle.parse(file("input.txt").readlines())

answer = puzzle.solve(data)

self.assertEqual(0, answer)

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

This is my basic template, I start each days puzzle with this code.

The puzzle.py defines two functions, because I split my solutions into two main parts. The first is to parse (that’s read and understand) the input file into a form or structure that I can use.

The second is to solve the puzzle with the input structure.

In the test code we do 3 things.

Firstly we import the unittest module and our puzzle file into scope. Where we say puzzle.something that will call a function in the puzzle file

Next we create a class to hold our tests. This can just be copied as is, but essentially it declares a class that inherits from the unittest.TestCase class, which the unittest framework uses to provide some features such as the asserts, and also to magically find our tests

Inside the class, we create a function called test_pass. It takes a single argument, which you can ignore, but that “self” is a standard python thing, we’ll use it in a minute

First we call the parse function in the puzzle module, and we use some of pythons built in modules to read the file and divide it into lines. If you create a file called input.txt and put some lines of stuff there, then that’s what would get sent to the parse function.

We take the return value of the parse function and call it data.

We then pass the data to the solve function and take that return value and call it answer.

We then compare the answer to 0 to see what it is.

Finally at the bottom of the file, there’s some code that says if this file is being run by calling python <filename> then run the unittest frameworks main function. It’s this that finds and runs all my tests

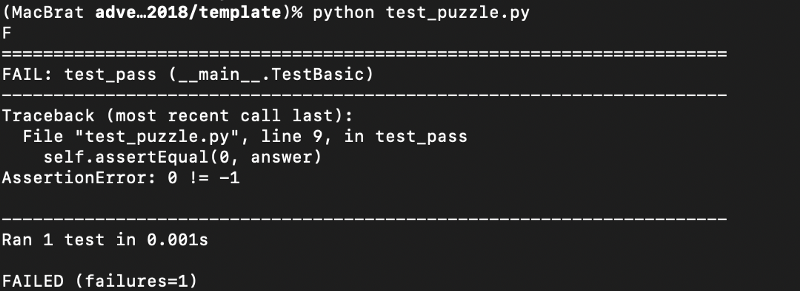

If you have those files, and create a file called input.txt (which can be empty) and type python test_puzzle.py it will run the tests and should fail, as below

This failed because we said we wanted to get a 0, but the puzzle.solve function returns a -1

I store all this code in a folder called ‘template’ and I simply copy it into a folder called ‘day1’ to try to solve day 1, and repeat each day. This makes it nice and easy to start again each day

Solving Day 1, Part 1

Ok, so the device starts with a frequency of 0, and we get given a list of numbers +1, -2 etc, and we want to know what frequency we end up on.

We could just model this exactly as described, take each number and apply it to our current frequency, and that’s probably the easiest way of doing so.

Mathematically, hopefully you remember that adding a negative number to something is the same as taking away the number? That means that (2)+(-1) should equal 1. That means we don’t need to do anything different for the + or -letters, we just need to turn them into the right kind of number.

This is what I mean by separating the puzzle into parse and solve parts. Our first problem is to take a text file filled with “+1, -3” and turn those into numbers that we can do maths on.

Python has a set of handy functions for this stuff, called the Python Standard Library, and in this case if you click the link to “numeric types”, you should see that there is a function called int(x), which is defined as “x converted to integer”.

Lets’ test this theory with a simple test,

def test_basic_parse(self):

data = puzzle.parse('''+1

+3

+2'''.split())

self.assertEqual([1, 3, 2], data)

If we add this code into our testcase (being careful around indentation, it should be indented one step from the class, the same as the other def test… code.

This is going to try using the parse function on the string

+1

+3

+2

Note that the ‘’’ characters start a “multiline text string”, which is important as it remembers the line breaks in between each character. The function expects a list of lines, so we need to call the split function before passing it into the parse function.

We pass that information to the parse function and expect back a list of the numbers [1, 3, 2]

If we run this test, it should fail and tell us that parse returned None, which is right, because we haven’t written that yet!

So let’s write that code shall we?

def parse(lines):

ans = \[\]

for line in lines:

ans.append(int(line))

return ans

We’re going to do this nice and simple. First we create an empty list. We can add things to the list using the append function.

Next we step through each line in the lines of data passed to us, and we turn it into a number and add the number to the list.

Let’s try running that test.

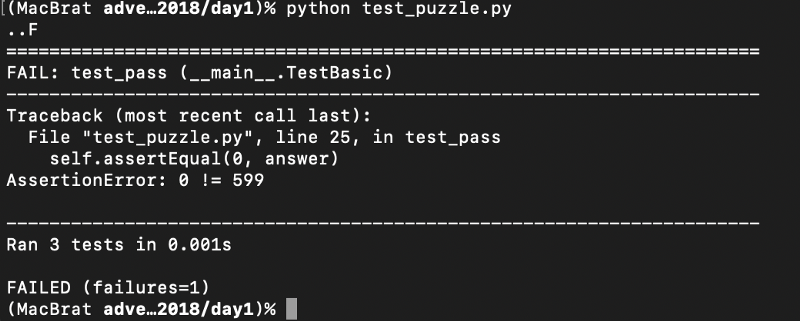

If we did this right, you should find that the test passed, but the original test is still failing. In unittests, you’ll get an output at the top, with passing tests represented by a . and failing tests with an F, so .F means that one passed and one failed.

So now we can turn the file into numbers, we can start doing maths on them!

Our solve function is going to be passed the list of numbers and needs to return the end frequency.

We could do this by running the real one, but let’s go slow. The AdventOfCode gives us some samples with known answers, so let’s try one. Add the following code to the test_puzzle.py file

def test_basic_solve(self):

data = [1, 1, -2]

self.assertEqual(0, puzzle.solve(data))

Re-running the tests should give you 3 failing tests, so let’s see if we can write the solve function.

We want to step through each number and add it to the total so far. The simplest possible code that can solve this is very similar the bit we just wrote:

def solve(data):

total = 0

for num in data:

total = total + num

return total

Now we’ve got a passing sample test, and our final test is showing something interesting. What’s that 599 answer? Well it’s the answer for my version of the code problem. Your number will be different because the Advent Of Code wants you to solve your own problems, not just look up the answers.

If you type your number into the Advent of Code website, you’ll have solved the first day!

Also, make that test pass, by writing the number 599 into the test, and you are good to go.

Part 2

I’m not going to solve day 1 part 2 for you, but it’s a more complex problem to solve.

I recommend starting by using a piece of paper and seeing how you would detect that you’ve hit the frequency a second time. I think the most likely thing is to keep a record of each frequency that you get to. A python dictionary with the key being the frequency and the value just being a simple “True” value should enable you to detect if you’ve seen that frequency before and promptly stop processing.

You’ll also need to have a go with the samples and make sure that your code will loop round the values more than once.

Best of luck, and I hope you enjoy it

You can get the code I’ve written over at my github page, although don’t look ahead to problems you haven’t solved. You can see people discussing the problems on the Advent of Code reddit page, and ask anyone you know to help